| Fitting a Shim |

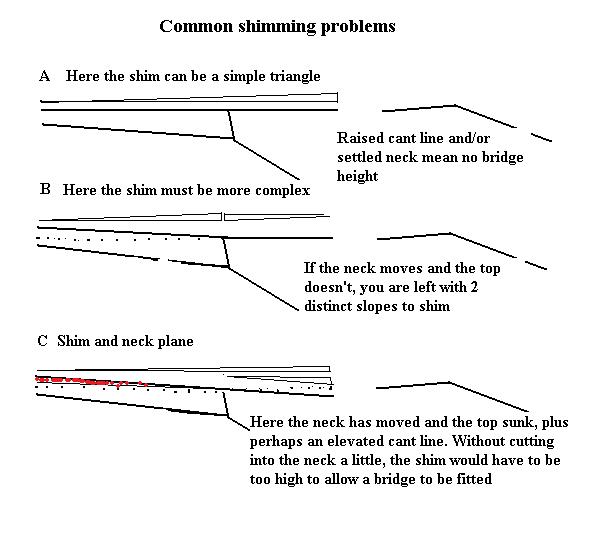

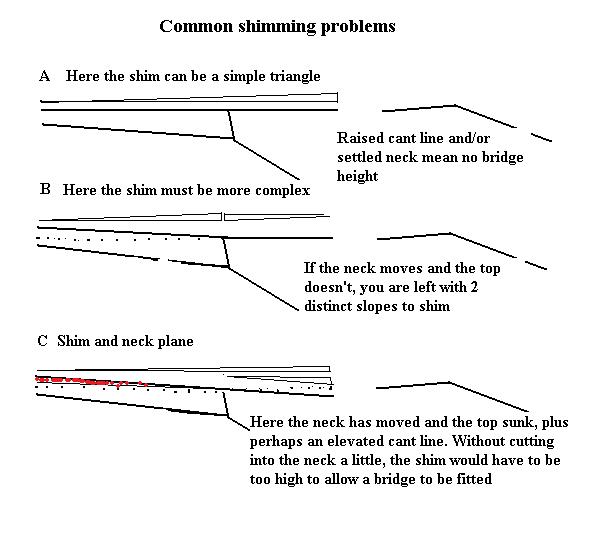

| The reason for fitting a shim, is

to raise the level of the board, particularly the bridge end, to give us a

better bridge height. It is often the preferable alternative to completely

re-setting the neck.... not easy on a bowl back. There are various

problems that must be considered when doing this............... |

|

|

|

|

| Here I have set up a steel rule, to

demonstrate the method I use to check potential bridge height. Often the

rule will rest on fret one and the bridge position, and not touch any

other frets. You must have a space under the ruler to be

able to fit a bridge. |

The first task is to remove the

fingerboard, with as little damage to board and neck as possible. Here it

has come away cleanly, but the old Italian bowls particularly, where

fingerboards are often very thin, have a tendency to break into pieces or

even crumble. |

Here an Italian fingerboard is being rebuilt

piece by piece on to a piece of rosewood, which will later form the shim,

after falling apart during removal. Sometimes this is inevitable, as the

fret-slots on thin boards often cut right through the board. |

|

|

|

| In order to bring the instrument back to

playability, a 'shim' needs to be fitted beneath the fingerboard to even

out any dip and raise the sound-hole end, allowing some room for the

fitting of a bridge. Often both ends of the 'shim' will need to be

carefully tapered before gluing. |

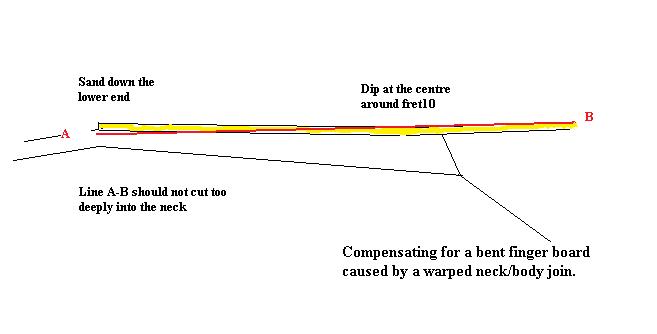

Another problem especially with Italian

finger boards, is that they are often not of a uniform thickness. This one

is about 3mm at the nut but only 2mm at fret 10. |

The material depends on that

used to make the neck, here a mahogany 'shim' is being made to fit a

mahogany neck, but I make from maple, ebony and rosewood. |

|

|

|

| I sometimes glue the 'shim' to the neck

first, but more often to the fingerboard, especially if it is a simple

triangle. That way it

is possible to keep the fingerboard top flat and level. Here a rosewood 'shim' is being glued to a rosewood

fingerboard, and the edges sanded level.

|

Here a half shim is glued to the mandolin

first, and brought to a level surface afterwards, by sanding. |

When the fingerboard and/or 'shim' are finally glued back into position, they are clamped to a

straight edge to keep everything level. The presence of the 'shim' will

help the neck maintain its position on the laminate principle. |

| NB. It doesn't make

any difference if you glue the shim to the fingerboard or the

mandolin, once the fingerboard is re-glued it is very likely

that you will have to either level the frets, or even re-level

the board. This is especially the case with Italian instruments,

as I am led to suppose that they were glued in place first, and then

levelled, thus evening out any inconsistencies in the neck mounting. Fret

slots would then be cut and frets fitted. This would explain why there are

often cuts in the neck when the f/b is removed, and why the f/b is often

not of a uniform thickness. |