Mandolins: A Brief History

|

The history of the mandolin |

|||||

|

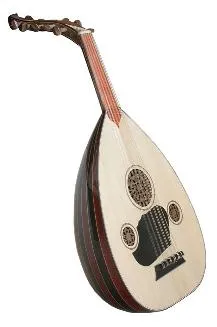

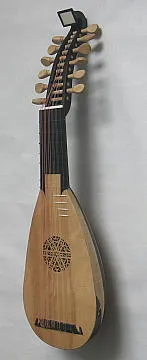

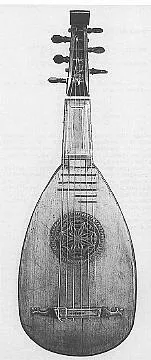

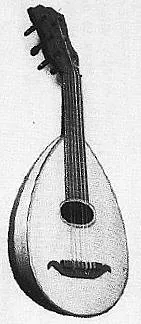

Its origin was probably the 'oud', which can still seen in the near east today, which after it's spread at the time of the Moorish invasions of Europe, evolved into various forms of lute during the middle ages. By the mid-sixteenth century, the small, shallow-bowled, high-pitched members of the lute family, originally 'gitterns' in England, and 'quinterns' in Germany, came to be known as 'mandora' or 'mandola', and 'mandores' in France. The smallest version was called the 'mandolina' in Italy.

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arabic Oud |

Oud | Gittern, J. Bisgood | Gittern | Mandore | Modern arabic buzuk |

|

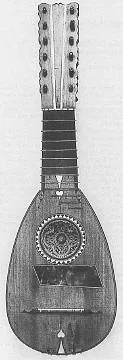

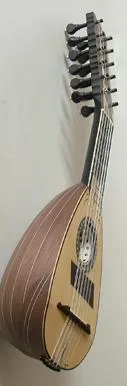

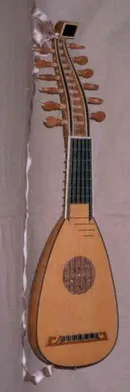

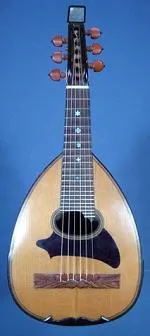

Most had 3 or four courses of gut strings, running over 7 to 9 frets on a flat fingerboard, to a reclining carved peghead. The scale length was about half that of the lute, and later strings were added in double courses. From about 1650, the mandores with 5 or 6 courses of double strings began to die out, but the soprano version became known as the mandolino continued to develop, and were tuned (gg) (bb) e'e' a'a' d"d" g"g". This is the instrument of Vivaldi's mandolin concerto. Milanese or baroque mandolin gradually developed with 6 of gut strings, tuned g b e' a' d" g". This in turn became the Lombardic mandolin (also called mandore) with 6 gut strings, still tuned g b e' a' d" g", from the beginning of the 19th century. It had a rounder body, raised fingerboard and often an oval sound hole, with no rosette.

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mandolino/pandurine | Mandolino (repro- L. Faria, Brazil) | Mandolino | Milanese mandolino | Lombardic mandolin | Lombardic mandolin/mandore |

|

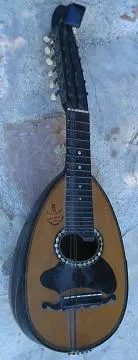

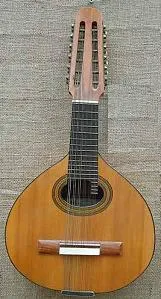

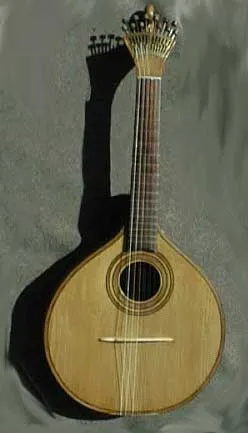

At the same time in France, a small instrument called a mandore developed, with 6 strings tuned E A d g b e'. The Genoses mandolin, with 12 strings and rear pegs also made an appearance in the 18th century, but did not last long. Another short-lived instrument was the Cremona mandolin with 4 strings tuned g d' a' e" .

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| French mandore | Genoevse mandolino (repro by Pandini | Genovese mandolino | Genovese repro | Cremona/Brescian mandolin | Cremonese by Cecconi |

|

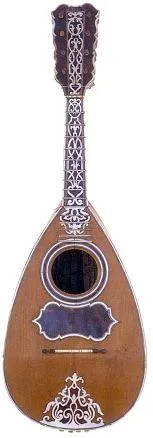

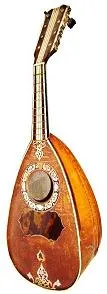

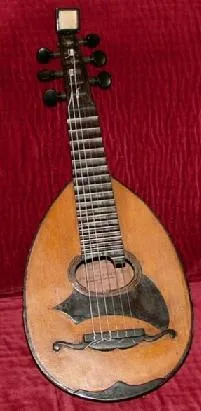

Finally in Naples, from all these strands, and the Turkish tanburs and buzoks, the Neapolitan mandolin was developed in the mid 18th century. The Neapolitan mandolin, which became so popular during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It seems to have been made from about 1760 onwards, with 8 frets, and a fingerboard flush with the belly. The mandolin had 4 double courses of metal strings, tuned in the violin tuning gg' d'd' a'a' e''e''. In the beginning, as it was difficult to get proper metal strings, the highest string was often made of gut. Important features were the cant in the top, to resist increased pressure from metal strings, and a floating bridge.

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Early mandolins/mandolinos from 1750s to 1850s | |||||

|

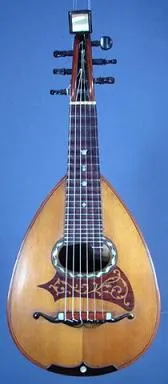

Nickel frets and geared metal machine heads improved the instrument from about 1850, replacing the rear pegs with initially enclosed, but later open tuners to the side. There was a fashion for oval sound holes and butterfly tortoise shell scratch-plates, sometimes backed with gold leaf, though many other scratch plate designs were current. It was played with a plectrum.

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Salsedo 1899 | Calace 1897 | U. Ceccherini | E. DE CRISTOFARO | G. Lingetti 189? | Maratea 1897 |

|

With the development of the 'modern' Neapolitan mandolin, it is important to remember, that all the other styles did not immediately cease to be made. Many of these different styles of mandolin existed side by side; the popularity of one declining gradually as the popularity of another rose gradually. Thus Lombardy and Milanese mandolins were still made right up to the end of the 19th century, as illustrated below.

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hybrid by S.Casini Firenze 19C | Lombardo by Cecconi | Milanese by Carlo Albertini 1870 | Milanese by Carisch & Janichen 19C | Milanese by Lavezzari 19C | Lombardo-esque by P. Gavelli |

|

In Spain, the early lutes seem to have evolved into the 'bandurria', a mandolin like instrument with 6 courses of strings, and the Portuguese 'guittara', larger than the mandolins, but both with the characteristic 'floating bridge'. It may have been the latter that led to the development of the flat back mandolin, from the original 12 stringed instrument. In Germany in contrast, the medieval lute seems to have evolved into the cittern, which remained little changed up to the 20C waldzither (or forest cittern) with characteristic double courses and floating bridge.

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jose Ramirez bandurria | Contreras bandurria | Portuguese guittaras | waldzither Hamburg type | Waldzither thuringer type | |

|

At the end of the nineteenth century, the mandolin moved to America with Italian immigrants, and became hugely popular. In 1900, a company called Lyon & Healy boasted 'At any time you can find in our factory upwards of 10,000 mandolins in various stages of construction'. They continued to be made in Italy by many famous violin-making families, and throughout the rest of Europe also. Almost all the mandolins made before 1900 were the traditional bowl-back design. At the turn of the century, an American, Orville Gibson, filed a patent that included a carved-top and flat back. This quickly became the industry standard in the States. The Gibson company made two styles of mandolins, each having the violin style of carved-tops and backs. The A-series mandolins had symmetrical bodies (also referred to as teardrops), and the F-series had a scroll on the bass side and two-points on the treble side. Each of these models had either a round or oval sound hole until the 1920s. The mandolinists of the era who were playing ragtime and dance tunes extolled the virtues of the Gibson mandolin, which was bigger and more powerful, but for the most part the classical mandolinists disliked it, because the long fingerboard made it impossible to play the more intricate, classical pieces. During twenties America, the banjo became more popular, with the explosion of jazz, and the popularity of the mandolin declined. Lloyd Loar, a mandolin virtuoso and an expert on the science of acoustics, joined the Gibson Company in 1919. It is said that he was the mind behind the F-5 mandolin and signed about 250 of them. The top of a Style 5 instrument was braced with two tone bars, versus one on the violin. The fingerboard raised off the top, as in violin design, allowed the top to vibrate more freely. The neck on the F-5 was significantly longer, with three more frets clear of the body than earlier Gibson models. The result was an instrument with an extremely rich and powerful tone that Gibson were never consistently able to reproduce after Loar left the company in December 1924. These instruments were, and are now, still highly prized, but the height of mandolin popularity had passed. It was to see a resurgence in America in the 40s when the mandolin was beginning to be used in a new form of country music called 'bluegrass'. The man who coined the term, William "Bill" Monroe, played his mandolin, a Loar F-5, very quickly, with brilliantly fast solo passages and a blues influence. Bluegrass and country music in America continue to ensure a place for the mandolin, whilst new mandolin orchestras are being formed in the style of the early twentieth century. In Europe, the folk and Celtic revivals have provided the same boost for the mandolin's popularity, and it continues to be made all over the world, in all of its various forms. Many thanks to John Troughton, Don Lashomb, Daniel Coolik and Mandolin Cafe, from whose articles this brief history has been cobbled together.

|

|||||