|

|

|

|

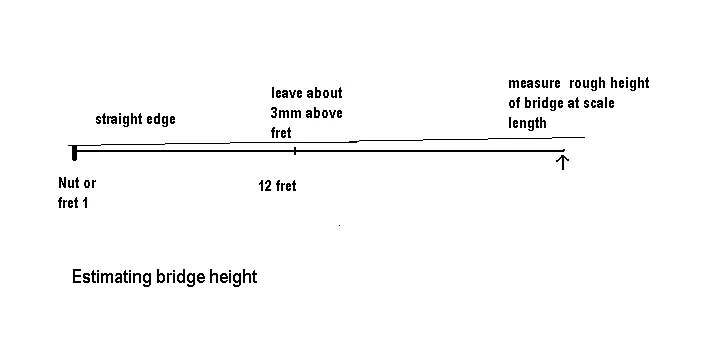

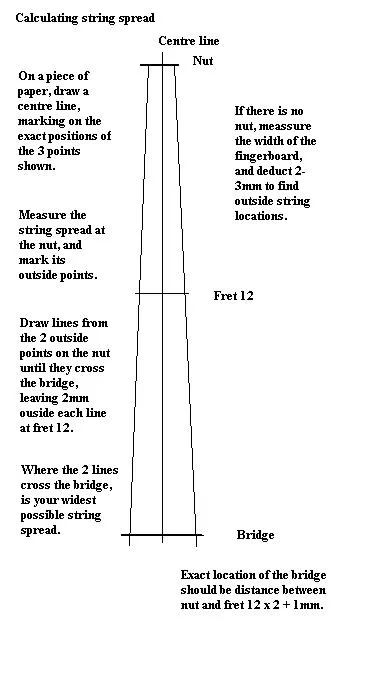

Fitting the Bridge Step 1: assuming you don't know the bridge height, place the long straight edge on the nut or 0 fret, raising it in the centre so that you are just over 3 mm above 12th fret, and measure the height above the table at the bridge position. (An extra pair of hands is useful here!) This gives you the approximate height of the top of the bridge saddle as a starting point.Step 2: chisel and/or file down your bridge foot until it is just a little bigger than you need, (a vice will help here!) Aim to get a dip to the centre to begin fitting to the curved top. Keep going back to the instrument with the bridge, to check where the high spots on the foot are. Chisel and/or file the centre much more than the ends to achieve a curve. Don't cut it down too fine yet!! |

|

|

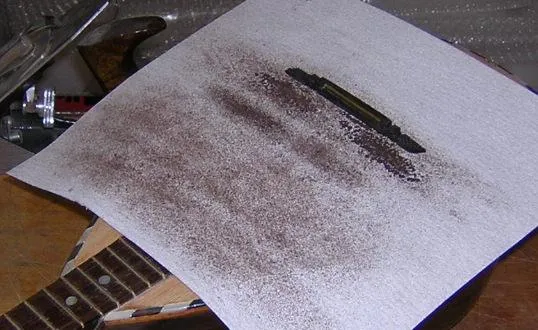

Step 3: hold or tape the sandpaper tightly to the table, and start rubbing the bridge back and forth across the sandpaper at the approximate bridge position. Use short strokes of perhaps 2-3cms back and forth. This should accurately contour the bridge's foot to the shape of the table once it is roughly chiselled to shape. I have found the easiest approach to this is to place the instrument in your lap between your legs, with the neck under your left arm... I'm right handed.You will need to remove the sandpaper to check the bridge's fit. Do so often now, as outlined in step 4. (NB. take care NOT to get sanding dust under the sandpaper when you are sanding, as this will seriously damage the surface of the table!) |

|

|

Step 4: using old strings if possible, and fit a top and bottom string just tight enough to hold the bridge in place. If the bridge's string slots are not already cut, you will need to do this now. (See below) Use the steel rule to measure the height of both strings above the 12th fret. Hopefully this should be a little over 2mm once they are in the slots. Remove the guide strings, and keep sanding down and checking until you get to the desired string height above fret 12. (On a mandolin, a good easy action is about 1.5mm at fret 12.) When you think its right, finish off with a fine grade paper, say 400 or 600. NB with a shelf bridge, almost all the adjustment needs to be to the bridge foot, though if you are careful, you can shave down the shelf itself a little. With an ordinary bridge with a bone saddle, it is possible to make fine adjustments to the string slots, and file down the saddle top a little if it becomes too high above the strings. |

|

|

Step 5: fit your new set of strings, with the bridge at its nominal position, and tune up gradually. For old instruments, used to the stress of strings, I usually do this in 3 or 4 stages over a couple of days. Check for any buzzes or rattles. Check the open string tuning with a tuner or pitch pipe. Also check the 12 fret note (an octave up) and the harmonic on the 12th fret. All should be very close to perfect. Do this for all strings. Unfortunately it is impossible to get everything absolutely perfect... different strings often need slightly different scale lengths.... the compensated bridges are one attempt to remedy this problem, but nevertheless, go for the best achievable balance. |

|

|

Once your bridge height is satisfactory, you may need to check the nut. The strings there can be safely lowered if you have level frets See Nut-fitting. |

|